A Spectacle of Mid-Career Innovation

Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch is a dazzling journalistic spectacle of color, design, and locution comprised of an obituary, a travel guide, and three feature stories. The obituary kicks the vignetted narrative off because it needs to set the stage for the following four sections. Why? Because the founder and editor-in-chief of the titular magazine, based in the fictional French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé (look up the translation for a chuckle), is dead at 75.

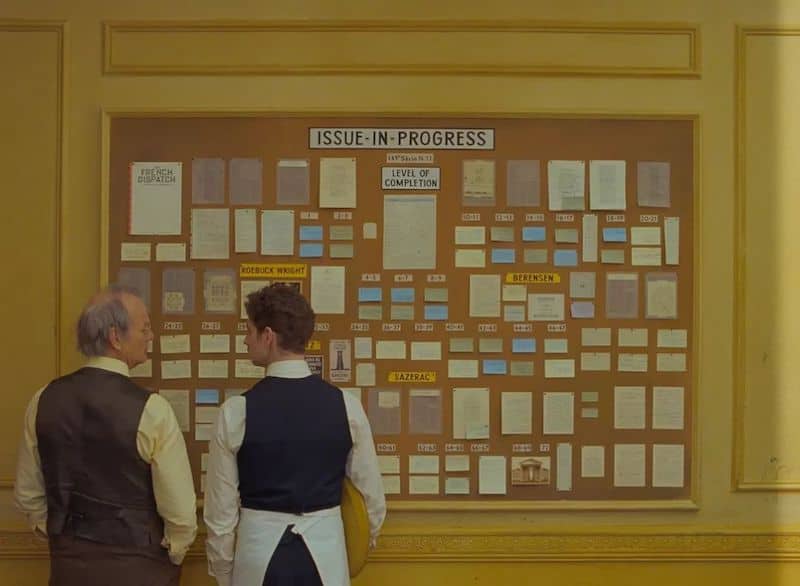

Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray) devoted his life to The French Dispatch and was chock full of industry advice. “Try to make it seem like you wrote it that way on purpose,” he’d say. Now that he’s gone, the operation is shutting down for good per his wishes, which means: one final issue. In pique Wes Anderson fashion, a narrator (voiced by Anjelica Huston) reads us through the articles at a silly rate. She rattles off mini-biographies, local histories, and statistics seemingly pulled out of a hat in a sheer fit of delight. It’s nearly impossible to follow everything on the first watch. Perhaps still so on the second and third.

In the same way that your favorite comedy churns out too many great jokes per minute to remember them all, The French Dispatch churns out creative detail and stories-within-stories ad infinitum. Your choice bits might get lost in the fray mere minutes later, but that’s because you’ve seen or heard ten more things you’ve loved since. No doubt that will only make rewatches richer.

After the obituary comes the travel guide — or the local section (only a couple pages) — written by Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson). Like all the writers of forthcoming sections, he takes over the narration while being heavily featured in the process. Often they’re talking to the camera or telling their story to others onscreen within the context of the film. For Sazerac’s part, he shows us around the sleepy town of Ennui-sur-Blasé to give us a sense of place.

And in what feels like no time at all, we then arrive at our first feature: “The Concrete Masterpiece” by J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) in the Arts & Artists section (pages 5-34). Benicio Del Toro, Léa Seydoux, and Adrien Brody lead the tale about a fictionally famous work of art titled Simone, Naked, Cell Block J, Hobby Room and the hushed convict-artist Moses Rosenthalter (Del Toro) behind it. If there’s one significant flaw to focus on in The French Dispatch, it’s that “The Concrete Masterpiece” is the best of all the stories. By coming first, it sets the following stories up for some emotional misconnection.

This doesn’t drag the other two down. It just keeps them from being their absolute best. But there are too many interesting things going on technically, stylistically, and literarily to be bored or disengaged.

The second feature is “Revisions to a Manifesto” by Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) in the Politics & Poetry section (pages 35-54). It focuses on factions in the pursuit of peace within a student protest body, led by Timothée Chalamet and French-Algerian newcomer Lyna Khoudri. Both are in good company with Del Toro, Elisabeth Moss, Jeffrey Wright, and others working with Anderson for the first time.

The third story, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” is written by Roebuck Wright (Wright) and featured in the Tastes & Smells section (I didn’t get those page numbers; have I mentioned this movie is fast and detailed?). I’ll leave that one up to your imagination.

Twenty-five years into the beloved boutique writer, director, and producer’s career, we know what to expect from Anderson. In his elaborate, utterly unmistakable style, the Houston-born filmmaker has become one of the most globally revered. So, almost everyone in the world knows what to expect. It also means he can do whatever he wants. Most filmmakers only dream of that kind of freedom, but it comes with a price, an embedded challenge. The pressure is always on to innovate.

Can he tell a new story that actually feels new? Can Anderson deliver his trademarks — wonderfully symmetrical framing; quirkily shot, labeled, and narrated listings of items; cameras dollying across neighboring sets; eccentrically dry comedic dialogue — and stack more on top to prove that his mind keeps moving? To affirm he’s as fresh and exciting now as he was when he began in the 1990s? That he won’t resort to banking on old tricks or suspiciously familiar IP? The answer, time and time again, is a resounding “yes!”

In fact, Anderson employs too many new tricks in his tenth feature to keep track of them all. But they’re imaginative and original in a way that you can only marvel at so deep into a veteran’s filmography. Especially when he would likely get away with settling. For example, he re-envisions the still frame in a way that allows him to dolly the camera across several neighboring (major air quotes) still-framed sets. Everyone is frozen yet struggling to stay still as if they’re in the final seconds of holding an impossible pose for too long. But it’s clearly intended for comedic effect, and it works.

Another new technique on display in The French Dispatch flips that relationship between the still and the kinetic. Static, layered, gorgeous shots seem empty at first, only for a flurry of people to eventually enter the frame. They might be a swarm of cops popping out of every hole one could squeeze into. Or the sluggish citizens of Ennui-sur-Blasé starting off their day. Both come as a pleasant shock when you initially thought there was no one there.

At one point, Anderson has a past version of a character trade clothes with a future version of a character as a creative means of showing us we’ve left the flashback and returned to the present. At another point, a full-blown animation sequence takes center stage. The film constantly switches back and forth between color and black and white cinematography. The latter is new for Anderson in this capacity and stands up visually against the best Pawlikowski films thanks to the work of all-timer director of photography Robert Yeoman.

In one of the more reflective moments of the film, a chef talks about experiencing a different taste for the first time. “A new flavor…that’s a rare thing at my age.” Someone thanks him, and he responds, “Don’t thank me. I just wasn’t in the mood to disappoint everyone.” You can practically hear Anderson’s voice come through. A flavor as new as The French Dispatch for someone so established and consistently creative is a rare thing. He’s right.

But it’s no surprise coming from him. It’s that desire to explore, to not disappoint, to find something new that enables Anderson to deliver rarity after rarity. And it’s that ever-growing collection of rarities that keeps him at the top among the most compelling and inspiring filmmakers working today.